Background of Japanese attack on Ceylon During Second World War

World War II, or the Second World War, began in Europe on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland. Two days later, on September 3, 1939, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany. The Second World War lasted six years and involved a vast majority of the world’s nations, including all of the great powers, eventually forming two major opposing military alliances; the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) were opposed by the Allied Powers (led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union). Five other nations joined the Axis during World War II: Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Croatia.

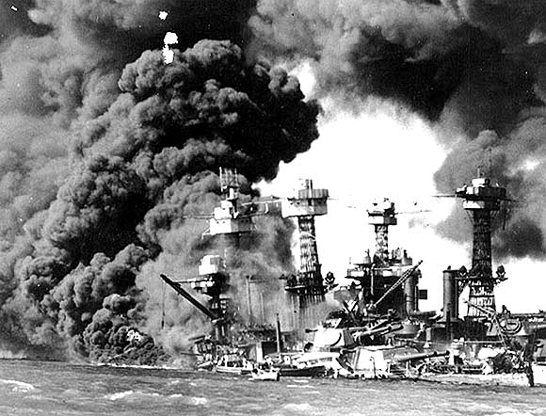

Japan formally entered the Second World War by attacking the United States Pacific Naval base at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu in the morning of December 7, 1941, which resulted in the United States and the United Kingdom declaring war against Japan. The attack on Pearl Harbor started at 7:48 a.m. Hawaiian time (6:18 p.m. GMT). They destroyed the US battleship Arizona and severely damaged the battleships Oklahoma, Nevada, California, and West Virginia, three destroyers, and nearly a dozen other naval craft. A total of 2,280 military personnel were killed and 1,109 wounded.

How many planes invaded Pearl Harbor?

The Japanese strike force consisted of 353 aircraft launched from four heavy carriers. These included 40 torpedo planes, 103 level bombers, 131 dive-bombers, and 79 fighters. The attack also consisted of two heavy cruisers, 35 submarines, two light cruisers, nine oilers, two battleships, and 11 destroyers.

Commencing with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the defeat of British forces in Malaya in January 1942, and the fall of Singapore on February 15, 1941, World War II entered the Indian Ocean and its epicentre, British Ceylon. The Japanese high command had planned a heavy bombing on Colombo very much like the Pearl Harbor operation. But luckily, much to the surprise and disappointment of the Japanese, the Allied naval fleet had been moved out of the Colombo harbor; thus, another Pearl Harbor was avoided. The survival of the British Eastern Fleet prevented the Japanese from attempting a major troop landing in Ceylon.

Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the Imperial Japanese Navy’s attack on Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as “the most dangerous moment in World War II.” He also went on to describe Canadian Squadron Leader Leonard Birchall as the “Saviour Ceylon” for his brave reconnaissance mission.

Related Post: Why did Japan fail to take Ceylon during the Second World War?

British Preparation for Japanese attack on Ceylon During Second World War

Ceylon was a strategically important hub for the British to impose their control over the Indian Ocean and the trading routes to India, South Africa, and Europe. Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, the East Indies naval fleet of the Allies was rushed, and a major Royal Navy base was established on the east coast at Trincomalee, one of the world’s biggest natural harbors. The Royal Air Force (RAF) soon established a “Catalina” (flying boat) squadron in early 1942, doing reconnaissance work from the Koggala seaplane base. The Koggala seaplane base was the largest “flying boat” station in Asia at that time. The other airbase facilities available at that time were the civilian airport at Ratmalana and the military airfield at China Bay in Trincomalee.

The Japanese attack on Malaya (now Malaysia), the Philippines, and the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) on December 7, 1941, changed the balance of power in the region drastically. Ceylon was expected to be the next Japanese target after Malaya (Malaysia) fell into the hands of the advancing Japanese forces on February 15, 1942. With the rapid advance of Japanese forces across Southeast Asia, the threat of an invasion of Ceylon, in particular the east coast around Trincomalee, meant that British forces on the island had to be significantly strengthened. With the loss of Malaya, Ceylon became the main source of rubber for the British.

Singapore had fallen on February 15, 1942, and two Royal Navy warships, the H.M.S. Prince of Wales and the H.M.S. Repulse, had been sunk off the eastern coast of Malay by Japanese aircraft, making Ceylon and southern India vulnerable to Japanese aggression. After the fall of Singapore, the Royal Navy’s Far Eastern Fleet set up headquarters in Ceylon. On March 16, 1942, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton was appointed as the first Commander-in-Chief of Ceylon, with Air Vice Marshal John D’Albiac Air Officer Commanding and Admiral Sir James Somerville appointed commander of the British Eastern Fleet. Under Vice Admiral Geoffrey Layton, the recruitment of military personnel gathered momentum to face a probable Japanese attack. Australian troops, on their way home after the battles in the Middle East, arrived in Colombo. East African troops also arrived around that time and took up “battle positions” in Ceylon.

Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville commanded three aircraft carriers, the modern H.M.S. Formidable and H.M.S. Indomitable, and the older H.M.S. Hermes. H.M.S. Warspite acted as the flagship of the Fleet, which also comprised four Revenge-class battleships. Somerville’s intention was to avoid direct contact and preserve his fleet.

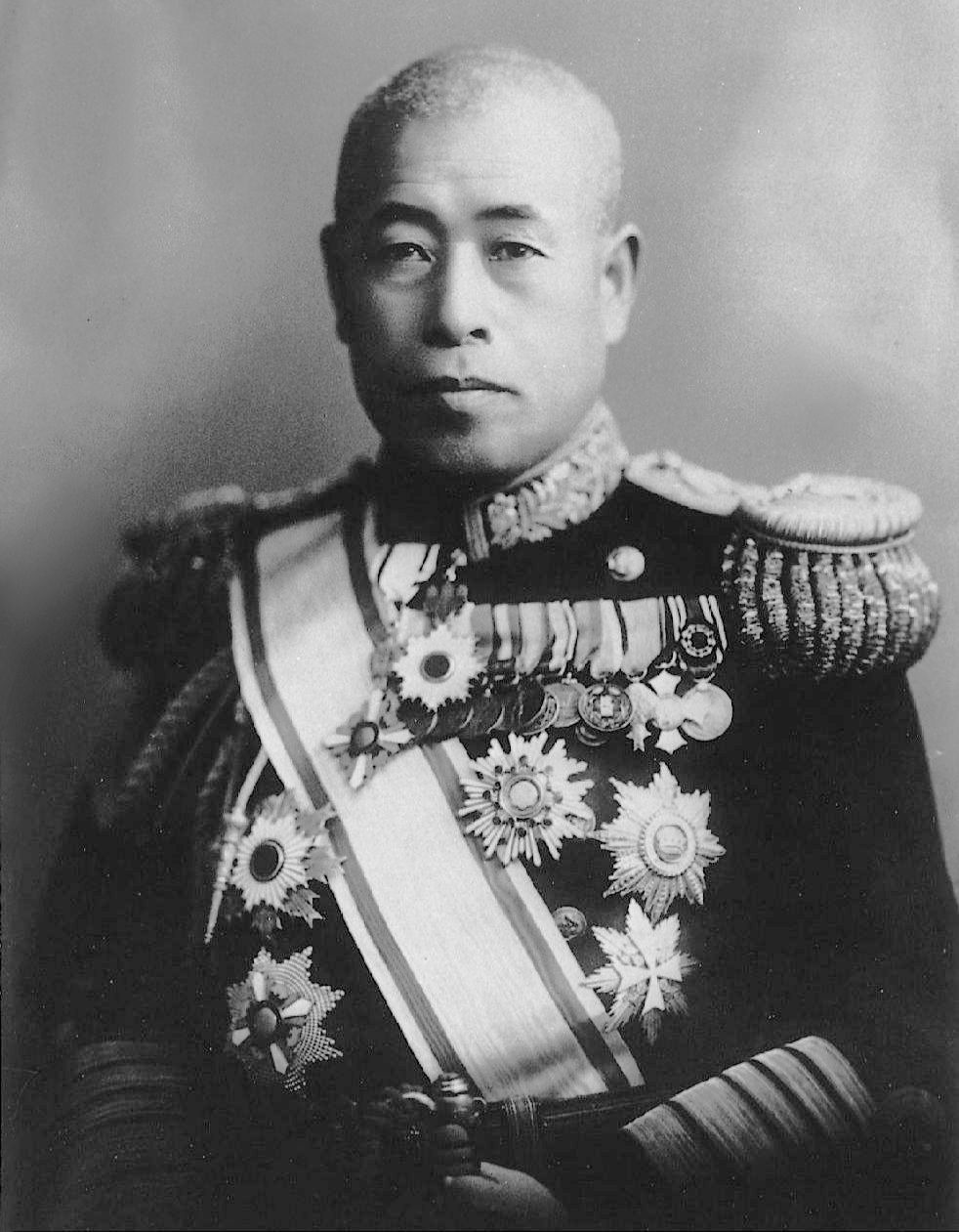

The Japanese were at Sri Lanka’s doorstep in the East with the capture of the Andaman and the Nicobar Islands by March 23, 1942, adding to the concerns about a probable invasion of Ceylon. Fortunately for the British, the Imperial Japanese Army was unable to allocate any troops to an invasion of Ceylon, so it fell under the Navy to carry out an offensive against the British in the Indian Ocean. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto commanded what was known as Operation ‘C’, which commenced on March 26, 1942. The intention was to attack the British Eastern Fleet in port at Colombo on April 5, and the Japanese were confident of being able to do so.

Commencing on March 31, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a major operation against the British Eastern Fleet, based at Trincomalee and Colombo. The Japanese fleet that was imminent comprised five aircraft carriers under the command of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the same two leaders who carried out the Pearl Harbor raid that resulted in the US entering World War II.

By April 4, 1942, the R.A.F. (Royal Air Force) and F.A.A. (Aircraft of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm) strength on Ceylon was sixty-seven Hawker Hurricanes and forty-four Fairey Fulmar fighters. There were also seven long-range Catalinas for reconnaissance, fourteen Bristol Blenheims, and twelve Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. The R.A.F. elements were part of No. 222 Group, commanded by Air Vice Marshal John D’ALBIAC. (Air Marshal Sir John Henry D’Albiac, (1894 – 1963) was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War.)

How was the Japanese attempt to invade Ceylon thwarted?

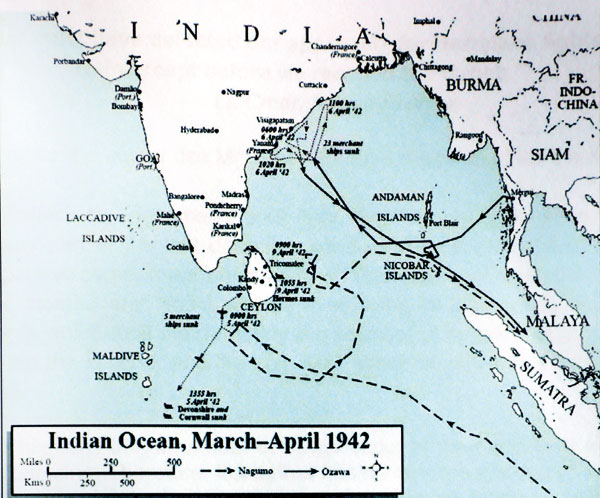

The Indian Ocean raid, also known as Operation C or Battle of Ceylon in Japanese, was a naval sortie carried out by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from March 31 to April 10, 1942. The Japanese attempt to invade Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was then called) was not only thwarted but successfully repulsed by the Allied Forces based on the island. Japanese aircraft carriers under Admiral Chūichi Nagumo attacked Allied shipping and naval bases around British Ceylon but failed to locate and destroy the bulk of the British Eastern Fleet.

The Japanese objective was to destroy the Ceylon-based British Eastern Fleet in the harbor. Allied intelligence gave advance warning of the Japanese force heading towards Ceylon in March but underestimated its strength. Vice Admiral Layton preemptively ordered the ships in the harbors at Colombo and Trincomalee to disperse to sea to avoid being attacked by Japanese in the harbor. This included the cruisers H.M.S. Cornwall and H.M.S. Dorsetshire, which sailed from Colombo, and the small aircraft carrier, H.M.S. Hermes, which sailed from Trincomalee with orders to hide north-east of Ceylon.

Spotting of Admiral Nagumo’s fleet

By April 2, 1942, Admiral Nagumo’s fleet was heading towards Sri Lanka in search of what remained of the British’s sea power in the East.

On April 2, 1942, Squadron Leader Leonard Joseph Birchall of the Royal Canadian Air Force came to Ceylon in his Catalina with his eight-member crew to the Koggala seaplane base. Two days later, on April 4, 1942, Birchall volunteered to fly out in his Catalina on a reconnaissance mission, patrolling an area 250 miles southeast of Sri Lanka. They took off from Lake Koggala, the Catalina base on the south coast of Ceylon. After completing his routine search mission and on his way back to base, Birchall spotted a series of “sticks” rising up on the distant horizon and against the dim grey evening skies about two hours before dusk.

Birchall suddenly turned his Catalina to take a closer look at the suspicious object and observed a Japanese armada (a military fleet) of seven aircraft carriers, three battleships, two cruisers, and a large number of destroyers heading towards the south-east coast of Ceylon, about 350 miles away. This was identified as the vanguard of Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s fleet. (Chūichi Nagumo was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. Nagumo led Japan’s main carrier battle group, the Kido Butai, in the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Indian Ocean raid and the Battle of Midway.)

Birchall radioed back to the base about the position and composition of the advancing Japanese naval fleet. His SOS message was picked up, and all “posts” in the island were alerted. While he was repeating the SOS a third time (as there was no reply to his earlier messages), spotting Birchall’s aircraft, six Japanese zeros, flying twice as fast as the Catalina, were soon in hot pursuit. Under attack by the Japanese fighters, the reconnaissance aircraft disintegrated, but before that, Birchall had already gotten the message of the presence of the Japanese fleet in Sri Lankan waters. The Catalina’s radio and navigational equipment sustained heavy damage, and the sea plane crashed into the sea into the sea near Hikkaduwa.

With darkness setting in, the courageous crew of the Catalina kept afloat in the Indian Ocean, about three hundred and fifty miles from land. One member of the crew was killed, while two others were killed by Japanese machine-gun fire while they were in the water. Fifteen minutes later, Birchall and five other survivors were picked up by a destroyer and later transferred aboard the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi to Japan. Three of the Catalina crew members were badly wounded.

The Japanese interrogated Birchall to find out whether a radio message had been flashed, alerting Ceylon about the pending invasion. Birchall said he was about to do so when the radio equipment was destroyed by the Japanese gunfire. During the intensive interrogation, the six prisoners denied that a radio message had been sent to Ceylon, alerting its air and ground forces.

Leonard Birchall, who was called the “Saviour of Ceylon,” was transferred to a Yokohama prisoner-of-war camp, where he was kept for about 15 months. The Japanese then moved him to Tokyo until the Allied forces virtually “burnt out” the capital. After Birchall and his surviving crew fell into the hands of the Japanese, all hopes of seeing them again had been given-up for nearly two years until a Canadian managed to escape from the prison camp and sent a postcard to “Mrs. Birchall C/o the war office,” stating “Birchall is Alive”. With the end of the war, Birchall and his remaining crew members were liberated by the American troops. Air Commodore Birchall has been widely described as the “Saviour of Ceylon” Birchall was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

What follows is Leonard Birchall’s own account of what happened next:

As we got close enough to identify the lead ships we knew at once what we were into but the closer we got the more ships appeared and so it was necessary to keep going until we could count and identify them all. By the time we did this there was very little chance left.” The Catalina was then attacked by up to 12 Zeros.

All we could do was to put the nose down and go full out, about 150 knots. We immediately coded a message and started transmission …We were halfway through our required third transmission when a shell destroyed our wireless equipment and seriously injured the operator; we were now under constant attack. Shells set fire to our internal tanks. We managed to get the fire out and then another started, and the aircraft began to break up. Due to our low altitude it was impossible to bail out, but I got the aircraft down on the water before the tail fell off”

The Canadian Hero Visits Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1992

In 1992, Leonard Joseph Birchall visited the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the air battle over Colombo. He was given a hero’s welcome by the Sri Lankans. He visited his former WW2 air base in Koggala and erected a monument that marked 50 th anniversary of the defense of Sri Lanka.

Japanese Attack on Easter Sunday 1942

On Easter Sunday, April 5, 1942, Japanese squadrons of bombers and fighter aircraft came in formation from two directions at about 7.30 a.m., led by Commander Captain Mitsuo Fuchida, attacked strategic targets in Colombo, including Colombo harbor and Ratmalana airport, badly damaging harbor installations. Devout Christians throughout the country were attending Easter Sunday morning services in churches and heard the drone of aircraft and the immediate loud wailing of police sirens fixed at junctions. The thunder-like sounds from anti-aircraft guns stationed at strategic points signalled that Emperor Hirohito’s mighty military forces, which had captured Hong Kong, Cambodia, Vietnam, Burma (now Myanmar), Siam (now Thailand), Malaya, Singapore, and a good part of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), were attacking the island of Ceylon. (Hirohito was the 124th emperor of Japan, reigning from 1926 until his death in 1989. He was one of the longest-reigning monarchs in the world, with his reign of 62 years being the longest of any Japanese emperor.)

When the air raid sirens sounded on that fateful Easter Sunday morning, some of those who were caught in the Colombo streets were at first inclined to ignore the warning as “just another rehearsal alert.” Instead of taking cover in the newly constructed underground air raid shelters, strategically located in various parts of Colombo city, they preferred to stand and gaze at the aircraft formation overhead. The Japanese, taking advantage of the low thunder clouds, carried out the first round of dive-bombing over Colombo harbor.

The Japanese aircraft carriers rearmed their planes with torpedoes, and at 11.45 hours, they started a second round of high-level bomb attacks, launched over Colombo. The Japanese were astonished when they were repulsed and driven off by repeated anti-aircraft gunfire. Unable to achieve the air superiority that they had hoped to achieve, the Japanese met stiff resistance and lost twenty-seven aircraft in the air battle, and the British too lost the same number.

Several Allied fighter aircraft were destroyed at Ratmalana. Thirty-six “Hurricane” fighter planes and six “Fulmar” aircraft from the recently-constructed airfield at the Havelock Racecourse found themselves engaged in the battle. While Ratmalana came under heavy attack, the Racecourse went unscathed, with Japanese intelligence unaware of its existence. On that same Easter Sunday afternoon, the merchant cruiser “Hector” and the destroyer “Tenedos” were sunk in Colombo harbor, while the cruisers “Dorsetshire” and “Cornwall” were sunk by dive-bombing, some 300 miles west of Colombo. The Allied losses in aircraft in the “Battle of Colombo” were officially stated to be “comparatively heavy.” The bulk of the British Eastern Fleet was not found and survived.

The Allied forces, warned of the danger, were able to shoot down some of the enemy aircraft, which fell on land and at sea. Among those shot down, one fell near St. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, one closer to the Bellanwila paddy fields, one near Pita Kotte, one on the Racecourse, one near Horana, and one on the Galle Face Green. One bomb fell off the target, mistaking it for the fuel tanks at nearby Kolonnawa, and damaged the Angoda Mental Hospital, killing some inmates. It was an accidental drop of a bomb by the Japanese, and on a later date, they apologized to the Ceylon Government.

By evening on April 5, 1942, the entire city of Colombo was virtually deserted. Most of the terrified civilian population—including dock workers — fled to the provinces by whatever transport they could find. These included buses, trains, cars, bicycles, rickshaws and bullock carts. Private cars were then far less than now and petrol was rationed under wartime conditions.

The Ceylon Daily News reported the raid on Monday, April 6, 1942:

“Colombo and the suburbs were attacked yesterday at 8 o’clock in the morning by 75 enemy aircraft which came in waves from the sea. Twenty-five of the raiders were shot down, while 25 more were damaged. Dive-bombing and low-flying machine-gun attacks were made in the Harbor and Ratmalana areas. A medical establishment in the suburbs was also hit. “

Japanese Attack on Trincomalee

The fleet attacked Colombo on Easter Sunday then sailed round the island to attack Trincomalee hoping to effect a second Pearl Harbor. The Allied forces in Ceylon next anticipated an attack on Trincomalee, and a large Japanese armada, both warships and aircraft carriers, was spotted on April 9, 1942, by reconnaissance planes, about 30 miles off the east coast. At 7 a.m., the Japanese unleashed their first attack on Trincomalee harbor, causing heavy damage with ninety-one bombers and thirty-eight fighter aircraft. However, in contrast to Sunday’s raid, the RAF at China Bay had received some advanced warning and already had a meager aerial force scouring the skies for enemy aircraft.

The fierce fight that ensued over the skies of Trincomalee that day claimed countless lives in the air, sea, and ground, with damage to fuel installations, ammunition dumps, vehicles on the ground, ships at the harbor, and aircraft that dropped from the sky like flaming meteors. One Japanese pilot is claimed to have committed suicide by crashing his plane into one of the Navy’s massive British oil storage tanks, which happened to be fully filled at that time. The airfield in China Bay came under heavy bombardment, but again, due to the timely warning by Birchall and the effective measures taken by Layton, the attack was repulsed.

The Allied forces using “Fulmars,” “Blenheims,” and “Hurricanes” engaged in fierce fights with the enemy aircraft, and Japan sustained losses of 21 war planes while 17 others were crippled in the Battle for Trincomalee. “Anti-aircraft fire from the ground had downed nine of the Japanese planes. Eight “Hurricanes” and three “Fulmars” of the Allied forces were destroyed, while five “Benheims” and a “Catalina” were reported “missing in action.” Six airmen of the ground staff were killed, while 36 were seriously wounded. The bombing caused heavy damage to hangars, equipment, and bomb dumps in the Trincomalee battle. A plane on the airstrip was destroyed. One section of the Trincomalee harbor was also badly damaged. The aircraft carrier “Hermes,” accompanied by the Australian destroyer “Vampire,” was spotted about 80 miles south of Trincomalee by the Japanese raiders on that same fateful date. Both of these vessels were sunk. They could not defend themselves, as the planes aboard the carrier, had already been sent to defend Ceylon. The corvette, “Hollyhock,” which was nearby, was also sunk.

The Navy sustained a total of 756 casualties in the two “battles” over Colombo and Trincomalee. Twenty-one officers and 287 ratings lost their lives on the “Hermes.”. Ten officers and 180 ratings were lost aboard the “Cornwall,” 19 officers and 215 ratings on the “Dorsetshire,” three officers and 12 ratings were killed aboard the “Tenedos,” and one officer and eight ratings perished with the “Vampire”. There were no casualties reported on the “Hector.”

A Japanese aircraft, believed to be on reconnaissance, flew over Colombo on July 17, 1943, and the following day, a Japanese bomber flew on a similar mission over Colombo. Another reconnaissance aircraft flew over Hambantota and Colombo on September 20, 1943. A “Beaufighter” belonging to the Allied forces shot down a Japanese naval aircraft on a reconnaissance mission on October 12, 1943. A Japanese seaplane was shot down 17 miles west of Colombo in November 1943. On February 7, 1944, a Japanese warplane flew over Point Pedro and later over Batticaloa. It dropped eight bombs, but there were no casualties as most of them fell on the Batticaloa-Trincomalee road and on a nearby plantation.

End of the Second World War

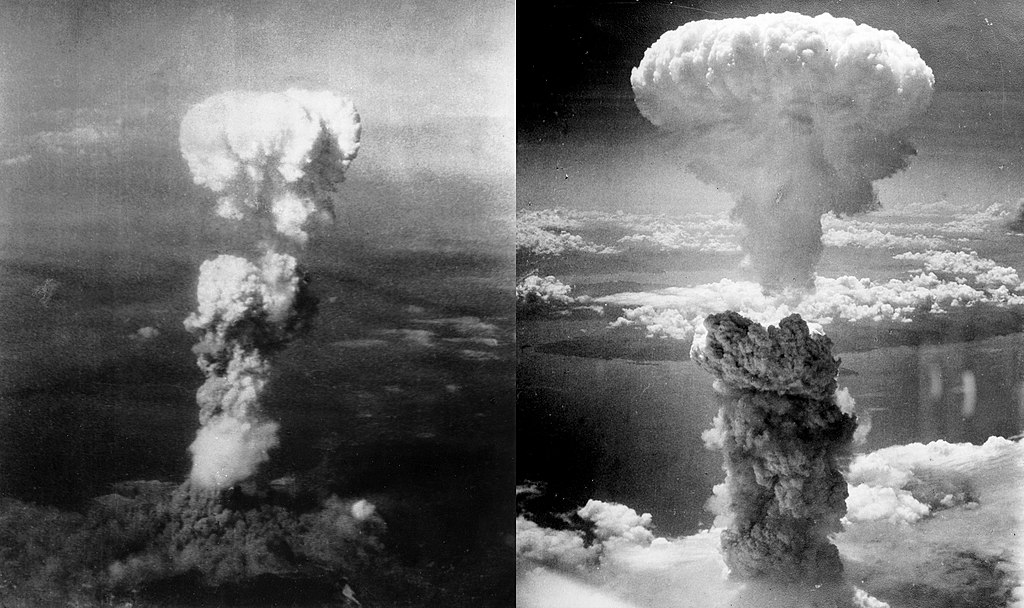

The United States produced the first atom bomb and successfully tested it in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945. On August 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the first atom bomb (a Little Boy), used in a war, on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. It killed more than 200,000 people. When military officials realized Japan would not surrender after the Hiroshima bombing, the decision was made to drop the second atomic bomb. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, a second atom bomb (a Fat Man) was dropped by the US on the industrial city of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 72,000 people, almost all of them civilians. Over the next two to four months, the effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000 to 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000 to 80,000 people in Nagasaki; roughly half occurred on the first day.

Five days after the Nagasaki bomb, on August 14, 1945, the Japanese unconditionally surrendered.

Japan publicly announced its surrender on August 15, 1945. This day has since been commemorated as Victory over Japan, or ‘VJ’ Day. On September 2, a formal surrender ceremony took place on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, officially bringing the Second World War to an end. World War II was the most widespread war and the deadliest global conflict in human history, with an estimate of at least 129,000 deaths recorded from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, and approximately six million Jewish deaths reported from the Nazi Holocaust.

Millions of people across the world celebrated the Allied victory over Japan in August and September 1945.

Reference(s): sundaytimes.lk | Wikipedia | britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk

Thanks for reading the post (Japanese attack on Ceylon During Second World War) and we’ll see you on the next one!

Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This blog post may contain other affiliate links as well by which I earn commissions at no extra cost to you.

Having read this I believed it was extremely enlightening.

I appreciate you spending some time and effort to put this content together.

I once again find myself personally spending a significant amount

of time both reading and commenting. But so what,

it was still worthwhile!

What’s up, I wish for to subscribe for this web site to take latest updates,

therefore where can i do it please help out.

If you wish for to take much from this article then you have

to apply these techniques to your won website.

Hmm it looks like your site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and

say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new

to the whole thing. Do you have any tips and hints for first-time blog writers?

I’d definitely appreciate it.

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This paragraph posted at this

web site is in fact pleasant.

I every time used to study post in news papers but now as I am a

user of internet so from now I am using net for posts, thanks to web.

I am actually glad to read this webpage posts which consists of tons of

useful information, thanks for providing these statistics.

hello!,I really like your writing very so much! share we be

in contact more approximately your post on AOL?

I require a specialist on this space to resolve my

problem. Maybe that’s you! Having a look ahead to look you.

It’s really a nice and useful piece of info. I’m happy

that you simply shared this helpful information with us.

Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have

found It absolutely useful and it has aided me

out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & help other customers like its helped me.

Good job.

I was suggested this blog through my cousin. I am not positive whether this post is written by him as nobody

else recognise such certain about my difficulty.

You are amazing! Thank you!

Hello my loved one! I wish to say that this post is amazing, great written and

come with almost all important infos. I’d like to peer more posts like this .

I do agree with all of the ideas you’ve presented for your post.

They are really convincing and will definitely work.

Still, the posts are too short for novices. Could you please extend them a little

from next time? Thanks for the post.