“From Pearl Harbor to Calvary” is Mitsuo Fuchida’s testimony of salvation

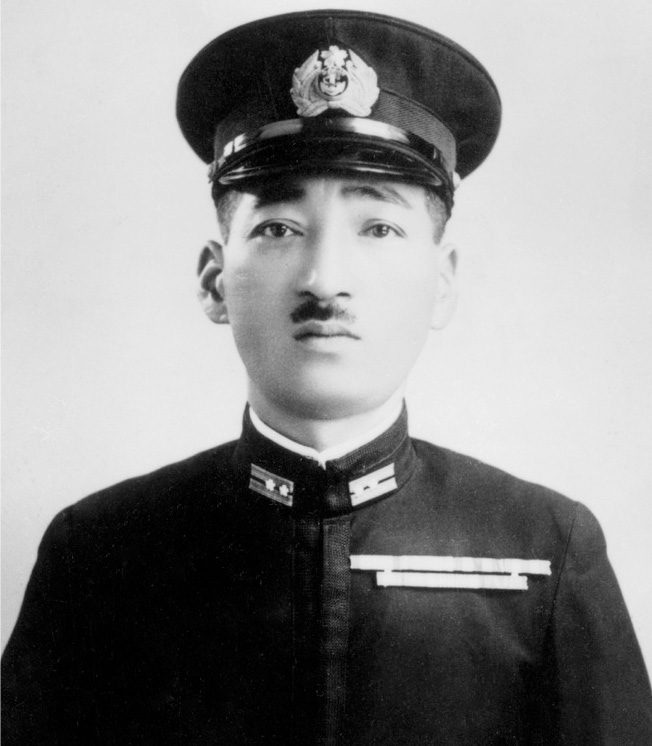

From Pearl Harbor to Calvary is the incredible story of Mitsuo Fuchida, a captain in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service who is perhaps best known for leading the first air wave attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Fuchida was responsible for the coordination of the entire aerial attack, working under the overall fleet commander, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. At 7:40 a.m. on December 7, 1941, he sent up the green flare from his plane signaling the order to attack and he later radioed back to the Japanese, said, “Tora, tora, tora,” meaning that the Japanese attack was a complete surprise. (Tora was the acronym for totsugeki raigeki, “torpedo attack,” and in Japanese, Tora means tiger.)

Captain Fuchida would stay over Pearl Harbor till the conclusion of the second wave of attacks, sustaining 21 various anti aircraft hits. Because of this success, he was granted an interview with the Japanese Emperor Showa. The Japanese captain would lead other Japanese carrier attacks as the fleet pushed further southward. At the Battle of Midway, appendicitis sidelined the heralded aviator, who watched from the bridge of the carrier Akagi. After it was hit, Fuchida began climbing down a rope, but an explosion threw him against the deck, breaking both ankles, ending his flight career.

The day before the Hiroshima atom bombing, Fuchida was attending a conference in the city but got called away to Tokyo. The day after, Fuchida returned with an assessment team to survey the damage, with all the others eventually succumbing to radiation poisoning.

After the war, Fuchida was summoned to Tokyo by General MacArthur, who was conducting war crime trials. The captain saw the war as over and said that Americans had been guilty too. He met his former flight engineer, who told him about an American, Peggy Covell, who had treated him well as a war prisoner, despite her missionary parents being killed by the Japanese in 1943. In fact, the parents had requested time to pray for their executioners. Fuchida saw Peggy as weak and failed to prove loyalty to her parents, by not seeking revenge, according to his moral code.

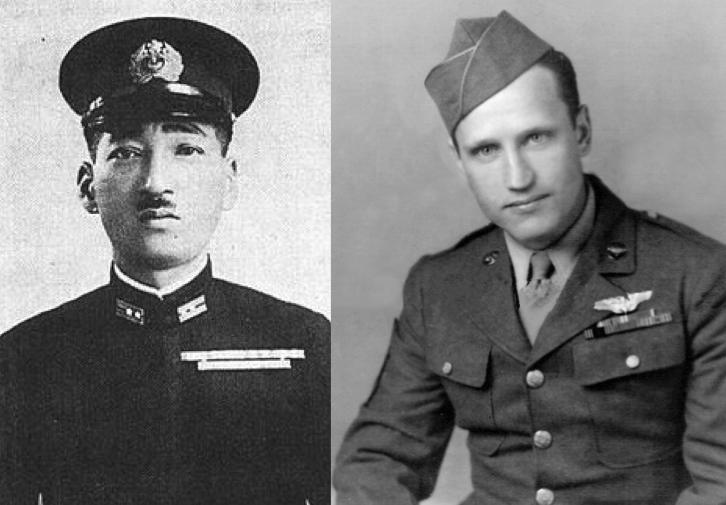

Once more, the Japanese captain was summoned to Tokyo to testify in 1948. There he received a pamphlet entitled I Was A Prisoner In Japan. It recounted the story of Jacob DeShazer, a member of Doolittle’s Raiders in 1942. DeShazer was captured in China by the Japanese, and managed to survive while some other members were killed or died of starvation. He asked for a Bible, and for three weeks he was permitted to read it. It changed his life. He learned Japanese, and some of the guards responded with less cruel treatment. After he was liberated, he went stateside and then returned to Japan to preach the gospel, establishing a church in Nagoya, the city he bombed as a Doolittle Raider.

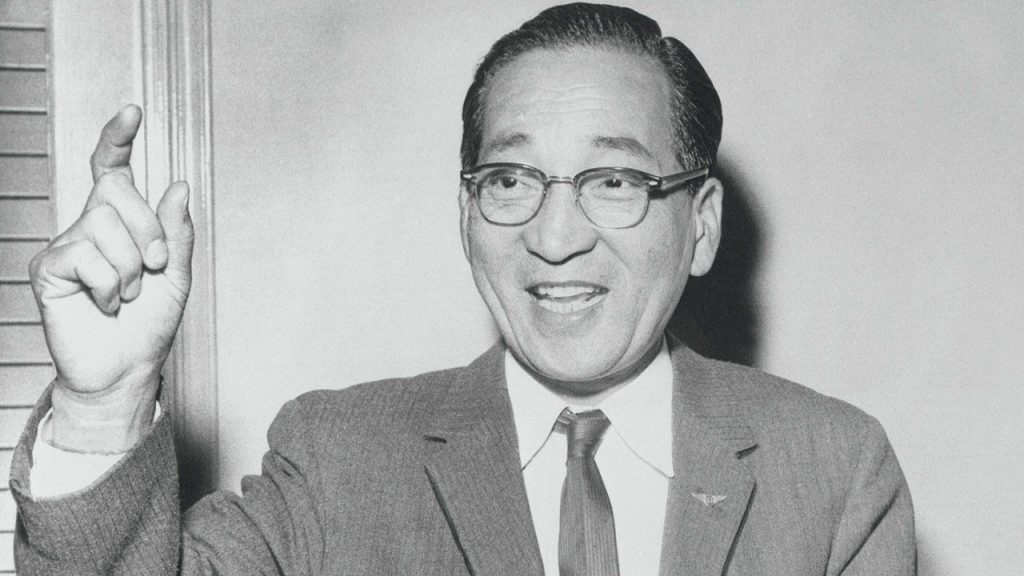

The stories of Peggy Covell and Jaob DeShazer influenced Fuchida to read the Bible. The gospels caused the captain to understand the principles of forgiveness that motivated Covell and DeShazer. In September 1949 Fuchida became a Christian. “Looking back,” he said later, “I can see now that the Lord had laid his hand upon me so that I might serve him.” Jesus’s words at the crucifixion, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing,” had a profound affect on the aviator, and on April 14, 1950, Fuchida accepted Jesus Christ as his Savior. He would become an evangelist, even embracing his former enemies. He wrote a booklet, From Pearl Harbor to Calvary, detailing his journey to accepting faith in Jesus.

From Pearl Harbor to Calvary: THE AMAZING STORY OF MITSUO FUCHIDA

I must admit I was more excited than usual as I awoke that morning at 3:00 a.m., Hawaii time, four days past my thirty-ninth birthday. Our six aircraft carriers were positioned 230 miles north of Oahu Island. As general commander of the air squadron, I made last-minute checks on the intelligence information reports in the operations room before going to warm up my single-engine, three-seater “97-type” plane used for level bombing and torpedo flying. The sunrise in the east was magnificent above the white clouds as I led 360 planes towards Hawaii at an altitude of 3,000 meters.

I knew my objective: to surprise and cripple the American naval force in the Pacific. But I fretted about being thwarted should some of the U.S. battleships not be there. I gave no thought of the possibility of this attack breaking open a mortal confrontation with the United States. I was only concerned about making a military success. As we neared the Hawaiian Islands that bright Sunday morning, I made a preliminary check of the harbor, nearby Hickam Field and the other installations surrounding Honolulu.

Viewing the entire American Pacific Fleet peacefully at anchor in the inlet below, I smiled as I reached for the microphone and ordered, “All squadrons, plunge in to attack!” The time was 7:49 a.m. Like a hurricane out of nowhere, my torpedo planes, dive bombers and fighters struck suddenly with indescribable fury. As smoke began to billow and the proud battleships, one by one, started tilting, my heart was almost ablaze with joy. During the next three hours, I directly commanded the fifty level bombers as they pelted not only Pearl Harbor but the airfields, barracks and dry docks nearby. Then I circled at a higher altitude to accurately assess the damage and report it to my superiors.

Of the eight battleships in the harbor, five were mauled into total inactivity for the time being. The Arizona was scrapped for good; the Oklahoma, California, and West Virginia were sunk. The Nevada was beached in a sinking condition; only the Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Tennessee were able to be repaired. Of the eight, the California, West Virginia, and Nevada were salvaged much later, but the Oklahoma, after being raised, was resunk as worthless. Other smaller ships were damaged, but the sting of 3,077 U.S. Navy personnel killed or missing and 876 wounded, plus 226 Army killed and 396 wounded, was something which could never be repaired.

It was the most thrilling exploit of my career. Ever since I had heard of my country’s winning the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, I had dreamed of becoming an admiral like Admiral Togo, our commander-in-chief in the decisive Battle of the Japan Sea. Because my father was a primary school principal and a very patriotic nationalist, I was able to enroll in the Naval Academy when I was eighteen. Upon graduation three years later, I joined the Japanese Naval Air Force, and served mostly as an aircraft carrier pilot for the next fifteen years. So when the time came to choose the chief commander for the Pearl Harbor mission, I had logged over 10,000 hours, making me the most experienced pilot in the Japanese Navy.

During the next four years, I was determined to improve upon my Pearl Harbor feat. I saw action in the Solomon Islands, Java, and the Indian Ocean; Just before the Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942, I came down with an attack of appendicitis and was unable to fly. Lying in my bed, I grimaced at the sounds of the firing all about me. By the end of that day, we had suffered our first major defeat, losing ten warships altogether. From that time on, things got worse. I did not want to surrender. I would rather have fought to the last man. However, when the Emperor announced that we would surrender, I acquiesced.

I was in Hiroshima the day before the atom bomb was dropped, attending a week long military conference with the Army. Fortunately, I received a long distance call from my Navy Headquarters, asking me to return to Tokyo. With the end of the war, my military career was over, since all Japanese forces were disbanded. I returned to my home village near Osaka and began farming, but it was a discouraging life. I became more and more unhappy, especially when the war crime trials opened in Tokyo. Though I was never accused, Gen. Douglas MacArthur summoned me to testify on several occasions.

As I got off the train one day in Tokyo’s Shibuya Station, I saw an American distributing literature. When I passed him, he handed me a pamphlet entitled I Was a Prisoner of Japan (published by Bible Literature International, known then as the Bible Meditation League). Involved right then with the trials on atrocities committed against war prisoners, I took it. What I read was a fascinating episode which eventually changed my life. On that Sunday, while I was in the air over Pearl Harbor, an American soldier named Jake DeShazer had been on K.P. duty in an Army camp in California. When the radio announced the sneak demolishing of Pearl Harbor, he hurled a potato at the wall and shouted, “Jap, just wait and see what we’ll do to you!”

One month later, he volunteered for a secret mission with the Jimmy Doolittle Squadron—a surprise raid on Tokyo from the carrier Hornet. On April 18, 1942, DeShazer was one of the bombardiers, and was filled with elation at getting his revenge. After the bombing raid, they flew on towards China but ran out of fuel and were forced to parachute into Japanese-held territory. The next morning, DeShazer found himself a prisoner of Japan.

During the next forty long months in confinement, DeShazer was cruelly treated. He recalls that his violent hatred for the maltreating Japanese guards almost drove him insane at one point. But after twenty-five months there in Nanking, China, the U.S. prisoners were given a Bible to read. DeShazer, not being an officer, had to let the others use it first. Finally, it came his turn—for three weeks. There in the Japanese P.O.W. camp, he read and read and eventually came to understand that the book was more than a historical classic. Its message became relevant to him right there in his cell.

The dynamic power of Christ, which Jake DeShazer accepted into his life, changed his entire attitude toward his captors. His hatred turned to love and concern, and he resolved that should his country win the war and he be liberated, he would someday return to Japan to introduce others to this life-changing book. DeShazer did just that. After some training at Seattle Pacific College, he returned to Japan as a missionary. And his story, printed in pamphlet form, was something I could not explain.

Neither could I forget it. The peaceful motivation I had read about was exactly what I was seeking. Since Americans had found it in the Bible, I decided to purchase one myself, despite my traditionally Buddhist heritage. In the ensuing weeks, I read this book eagerly. I came to the climactic drama—the Crucifixion. I read in Luke 23:34 the prayer of Jesus Christ at His death: “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.” I was impressed that I was certainly one of those for whom He had prayed. The many men I had killed had been slaughtered in the name of patriotism, for I did not understand the love which Christ wishes to implant within every heart.

Right at that moment, I seemed to meet Jesus for the first time. I understood the meaning of His death as a substitute for my wickedness, and so in prayer, I requested Him to forgive my sins and change me from a bitter, disillusioned ex-pilot into a well-balanced Christian with purpose in living.

That date, April 14, 1950, became the second “day to remember” of my life. On that day, I became a new person. My complete view of life was changed by the intervention of Christ, whom I had always hated and ignored before. Soon other friends beyond my close family learned of my decision to be a follower of Christ, and they could hardly understand it. Big headlines appeared in the papers: “Pearl Harbor Hero Converts to Christianity.” Old war buddies came to visit me, trying to persuade me to discard “this crazy idea.” Others accused me of being an opportunist, embracing Christianity only for how it might impress our American victors.

But time has proven them wrong. As an evangelist, I have traveled across Japan and the Orient, introducing others to the One who changed my life. I believe with all my heart that those who will direct Japan—and all other nations—in the decades to come must not ignore the message of Jesus Christ. The youth must realize that He is the only hope for this troubled world. Though my country has the highest literacy rate in the world, education has not brought salvation. Peace and freedom, both national and personal, come only through an encounter with Jesus Christ.

I would give anything to retract my actions of twenty-nine years ago at Pearl Harbor, but it is impossible. Instead, I now work at striking the death-blow to the basic hatred which infests the human heart and causes such tragedies. And that hatred cannot be uprooted without assistance from Jesus Christ. He is the only one who was powerful enough to change my life and inspire it with His thoughts. He was the only answer to Jake DeShazer’s tormented life. He is the only answer for young people today.

Related Post: Japanese attack on Ceylon During Second World War

Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This blog post may contain other affiliate links as well by which I earn commissions at no extra cost to you.